Layers of abstraction: Building a Python wrapper for the PDB search API

I'm a man who enjoys a well-designed software library API. I am also (if my academic history is to be believed) a structural biologist. That makes large, high-quality structural biology datasets like the Protein Data Bank, with powerful search web APIs in front of them, ready to be wrapped in a Python library, of enormous interest.

This post describes the process of creating such a Python wrapper around an existing API, to make it easier than ever to find precisely the structure you are looking for. I thought I would use it as a way to outline what I look for in a library, and the ways I think they should shield the user from precisely the right amount of complexity - no more, no less.

The Protein Data Bank

Firstly, what are we even doing here? What is the Protein Data Bank, what is RCSB, and what are we actually searching here?

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) stores protein structure information. Actually not just proteins, it's any large molecule, but this post is too long already, so I'm going to simplify. Each entry in the data bank contains the three-dimensional structure of one or more large molecules - specifically by giving x/y/z coordinates for every atom in the molecules. These coordinates are determined by an experiment, using X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy. There is also a lot of annotation within the files - each molecule is an instance of some named entity, which can either be a polymer entity (a long chain made up of subunits) or a non-polymer entity (usually just a small molecule), and each has a name, description, polymers have sequence information etc.

A large molecular structural, with each of its atoms' locations visualised. In this case it is a protein pore molecule.

The Protein Data Bank is a global organisation - research groups from all over the world do experiments and then submit structures to it, for anyone else in the world to access. At a quarter of a million structures stored in the data bank now, it is one of the most valuable and impactful biological datasets ever constructed. These structures are used in drug discovery, in basic research about how biological systems work, and as training data for some of the most important machine learning algorithms currently being developed - most notably AlphaFold.

The data bank itself is something of an abstract concept. Custody of it is split between three organisations - the European PDBe, the Japanese PDBj, and the American RCSB. There is one central repository, but you actually submit your structures to one of these three organisations, who assess it before adding it to the data bank. Each of the three maintains their own website, their own portal to the data, and their own web services for interacting with the dataset.

We are interested here, specifically, in RCSB's web services. Searching this incredibly valuable dataset is clearly very useful, and being able to perform very powerful, very precise searches is thankfully something they make available through their search API.

The Search API

The search API RCSB provides is somewhat simple in operation, though it can do powerful things. You send a single JSON object describing your query in a POST HTTP request, and you get a list of identifiers back. For example, here is a search object:

{

"query": {

"type": "terminal",

"service": "full_text",

"parameters": {

"value": "thymidine kinase"

}

},

"request_options": {

"paginate": {

"start": 10,

"rows": 3

}

},

"return_type": "entry"

}...and here is what you get back...

{

"query_id": "55478744-2e5e-42cc-b2f4-732c1f4e29cc",

"result_type": "entry",

"total_count": 693,

"result_set": [

{

"identifier": "4UXI",

"score": 0.9902022513036222

},

{

"identifier": "1E2J",

"score": 0.9901109053121924

},

{

"identifier": "1KIM",

"score": 0.9898382505620011

}

]

}In our query we asked for all entries that contained the text "thymidine kinase", and told it we want 3 results, after skipping the first ten. It returned these three results - the entry identifier and score showing how close the match was for each, as well some minimal metadata about how many total matches there are for this query.

We provide three attributes in our search:

query- this is your description of your search criteria. As we will see there are many ways to search, and you can combine multiple criteria. This is a single 'node', but you can combine these nodes with any combination of AND and OR you like.request_options- this describes how you want your results - pagination, sorting etc.return_type- what kinds of object you are searching. Theentryis entire PDB entries, but you can searchpolymer_entityto search for specific types of polymers within entries,non_polymer_entity,assemblyetc. On the backend, the API is quite smart about applying your search criteria to the specific type of object you are requesting.

You can, of course, already interact with this web API with Python, by constructing HTTP requests yourself with something like the requests library, or indeed with the py-rcsb-api library that RCSB provides. Both are quite low-level however, and as library API design is something of a hobby of mine, I wanted to try my hand at the problem. This is not in any way to disparage py-rcsb-api - it's an excellent library, which also supports an entirely different data API, which my implementation won't. I just like making Python libraries, and I wanted to add a little simplification of interface over the official one.

pdbsearch is a library I started a few years ago, for a previous version of the search API, but which is now out of date. It was also never entirely comprehensive. So, I thought I would rewrite pdbsearch from scratch to support it - while documenting my process, and what I look for in a Python library's interface.

Let's begin.

Basic search function

What is the absolute minimal, valid search object? It's this: {"return_type": "entry"}. Let's start with a functionality that can just do this, and build from there:

import requests

SEARCH_URL = "https://search.rcsb.org/rcsbsearch/v2/query"

def search(return_type="entry"):

query = {"return_type": return_type}

return send_request(query)

def send_request(query):

response = requests.post(SEARCH_URL, json=query)

if response.status_code == 200:

return response.json()We keep the logic for actually talking to the API over the network separate from the function that constructs the query, and create a search function which just returns the JSON of the most basic request - the first ten of whatever object type the user provides:

# Get ten entries

results = pdbsearch.search()

# Get ten polymer entities

results = pdbsearch.search("polymer_entity")Request Options

Before diving into how searching actually works, let's look at those request options. These are instructions on how the results should be returned - sorting, pagination etc. For now I just want to get the machinery for doing this in place - we can make it exhaustive later.

The option to return all results, and the pagination options start and rows seem simple enough. A separate function will construct the request_options object based on whatever parameters the user passes:

import requests

SEARCH_URL = "https://search.rcsb.org/rcsbsearch/v2/query"

def search(return_type="entry", **request_options):

query = {"return_type": return_type}

if request_options := create_request_options(**request_options):

query["request_options"] = request_options

return send_request(query)

def send_request(query):

response = requests.post(SEARCH_URL, json=query)

if response.status_code == 200:

return response.json()

def create_request_options(return_all=False, start=None, rows=None):

request_options = {}

if return_all: request_options["return_all_hits"] = True

if (start is not None) or (rows is not None):

request_options["paginate"] = {}

if start is not None:

request_options["paginate"]["start"] = start

if rows is not None:

request_options["paginate"]["rows"] = rows

return request_optionsNote that we only add the request_options object to the query if it has anything in it, and we pass any keyword argument to search that we don't have use for to create_request_options. So it now works like so:

results = pdbsearch.search("entry", return_all=True) # Get every PDB entry

results = pdbsearch.search("polymer_entity", start=100, rows=50) # 50 results, page 3But the library is called pdbsearch - so how do we actually... search?

Queries and Nodes

Here is another example query object, from the API documentation:

{

"type": "terminal",

"service": "full_text",

"parameters": {

"value": "thymidine kinase"

}

}This is a node - in this case a 'terminal' node (because it's a leaf in a possible tree of nodes - we'll come back to this later). It describes a single search criterion - searching for entries that contain the text 'thymidine kinase', in this example.

The service refers to which of the RCSB search services the query is for. The API provides a number of ways of searching, with this 'full text' service being the simplest.

The parameters contain the actual search criteria themselves, which make sense in the context of whatever service you are using. For example, with the full-text service, you only need the value parameter, but the others have more complex parameters.

Let's create a class to represent this. In general, I am not a fan of defining classes for every single concept or entity in a codebase, as they add complexity that rarely pays for itself, and increase the mental resources a developer needs to allocate to internalising a mental model of how the library works. However in this case, as we are going to be combining and merging them later on, it makes sense to treat them as pdbsearch's one primary object type.

@dataclass

class TerminalNode(QueryNode):

service: str

parameters: dict

def serialize(self):

return {

"type": "terminal",

"service": self.service,

"parameters": self.parameters

}Let's also update the search function to actually use a node like this. I will rename it to query, as this is now a function for running a single query (we will re-use the search name later for more complex operations):

def query(return_type="entry", node=None, **request_options):

query = {"return_type": return_type}

if node: query["query"] = node.serialize()

if request_options := create_request_options(**request_options):

query["request_options"] = request_options

return send_request(query)So we can now perform a search against the API like this:

node = TerminalNode(service="full_text", parameters={"value": "thymidine kinase"})

results = pdbsearch.query(node=node, return_all=True)This will construct a full, valid search API JSON object, send it to the API, and get all the results back as JSON. It has everything we need to perform a single, simple search.

However, it's very... wordy. The user has to import the TerminalNode class, create an instance of it, and pass that to the query function. They have to know what the correct instantiation arguments are, and now they have to know what a 'terminal node' is. They just want to search for entries with this piece of text, we shouldn't require them to have to understand how the API works in this level of detail - otherwise they might as well just talk to the API directly themselves, and this library adds no value.

Why not create a helper function:

def full_text_node(term):

return TerminalNode(

service="full_text",

parameters={"value": term}

)Now to create a request and send it to the API to get results, all the user needs to do is:

node = full_text_node("thymidine kinase")

query("entry", node, rows=5)This also solves the problem of having a class in the library at all - it is now essentially a hidden implementation detail, and the only time a developer would need to instantiate one directly would be if they already know how the API works and therefore already have a sound mental model.

We can do a little better though, as they are still having to perform two actions (make a node, then run query with it) when conceptually they just want to do one thing (search). We can add a query method to nodes, so that a node object can execute itself as a query, which is just a thin wrapper around our original query function:

@dataclass

class TerminalNode(QueryNode):

service: str

parameters: dict

def serialize(self):

return {

"type": "terminal",

"service": self.service,

"parameters": self.parameters

}

def query(self, return_type, **request_options):

return query(return_type, self, **request_options)So now the full, round-trip full-text search is just:

full_text_node("thymidine kinase").query("entry", rows=5)Much better.

The Other Search Services

What about the other search services? Most of them are straightforward (at least from the point of view of calling them - some of them do very complex things behind the scenes on the RCSB servers to actually do the search). For example, the 'sequence' service lets you provide a protein, DNA or RNA sequence, and find results that have polymers with that sequence, to a given tolerance:

{

"type": "terminal",

"service": "sequence",

"parameters": {

"sequence_type": "protein",

"value": "MNGTEGPNFYVPFSNKTGVVRSPFEAPQYYLA",

"identity_cutoff": 0.3,

"evalue_cutoff": 0.1

}

}(Here identity_cutoff and evalue determine how close a match should be allowed.)

We can create a similar function for creating sequence nodes, but we can do better than just having the user provide all four parameters - why not give the sequence type and the sequence itself in one go by passing protein="MNGTEGPNFYVPFSNKTGVVRSPFEAPQYYLA". We make protein, dna, and rna all keyword arguments, and whichever one is actually used, that's the sequence type:

def sequence_node(protein=None, dna=None, rna=None, identity=None, evalue=None):

sequence = protein or dna or rna

if not sequence: raise ValueError("Sequence not provided")

if sum(bool(x) for x in [protein, dna, rna]) > 1:

raise ValueError("Only one sequence type can be provided")

sequence_type = "protein" if protein else "dna" if dna else "rna"

parameters = {"sequence_type": sequence_type, "value": sequence}

if identity is not None: parameters["identity_cutoff"] = identity

if evalue is not None: parameters["evalue_cutoff"] = evalue

return TerminalNode(service="sequence", parameters=parameters)We can use this function like this:

pdbsearch.sequence_node(protein="MALWMRLLPLLALLALWGPDPAAA").query()

pdbsearch.sequence_node(dna="ATGCATGCATGC").query()

pdbsearch.sequence_node(rna="AUGCAUCGAUGC", identity=0.95, evalue=1e-10).query()I won't go through all of the search services in such detail. The sequence service gives an example of the kinds of interface I want to provide: make the user have to worry about only what they need to concern themselves with, and simplify the interface as much as possible, but no more. Similar helper functions were created for:

- The sequence motif service, where instead of providing a sequence you provide a more flexible sequence pattern and search with this.

- The structure service, where you provide the identifier of an existing PDB and an assembly within it, and find structures similar to it.

- The structure motif service, where you provide a specific pattern of residues (the monomers in protein polymers) and search for structures with a similar arrangement of atoms.

- The chemical service, where you provide a SMILES or InChI string (text descriptions of how atoms in a small molecule are connected) and find results containing those molecules.

All of these services are treated using the same pattern - we create a function that creates a TerminalNode from parameters that approximate the API specification parameters, and which can then be passed to the query function and run.

We are missing the most important search service however - the text service.

For the text service, you take one of around a hundred attributes defined by RCSB, and search by value. For example, the rcsb_assembly_info.polymer_entity_count attribute refers to the number of polymer entities in a structure, or the rcsb_accession_info.initial_release_date which refers to the release date.

The query object looks like this at the end:

{

"type": "terminal",

"service": "text",

"parameters": {

"attribute": "exptl.method",

"operator": "exact_match",

"value": "ELECTRON MICROSCOPY"

}

}The attribute is the object property you want to search, the value is the value of that property you want to filter by, and the operator defines how you want to apply that filter (greater than, within range etc.).

How should our text_node function handle this? We could have it take parameters for attribute, operator, and value - but in the same spirit of simplifying the interface, why not just combine them all into one?

# Meh

node = text_node(

attribute="rcsb_accession_info.initial_release_date",

operator="greater",

value="2008-09-28"

)

# Wowsers trousers

node = text_node(rcsb_accession_info__initial_release_date__gt="2008-09-28")We can't have dots in keyword argument names, so we use double underscore for these, and we also encode the operator into the keyword again using double underscores. The logic for parsing this is mildly more complex than the other service functions, but it's the sort of problem that is very amenable to comprehensive unit testing.

Each of the operators has a mostly straightforward suffix, though we have to handle a bit of complexity with some of them. The range operator, for example, has a four attribute object as its value (lower bound, upper bound, include lower, include upper). Rather than making the user construct this themselves, we can just have them give a list of the bounds: __range=[10, 20]. But what about the inclusive/exclusive information? Well, it's a little bit cheeky, but in mathematical notation () is used for exclusive ranges, and [] for inclusive ranges - so we can just make tuple exclude the bounds and a list include the bounds. It means they both have to be the same now, but if that's really an issue the user can make a node object from scratch.

# Get those with compounds that have between 10 and 20 bonds (inclusive)

text_node(rcsb_chem_comp_info__bond_count__range=[10, 20]).query()

# Get those with compounds that have between 10 and 20 bonds (exclusive)

text_node(rcsb_chem_comp_info__bond_count__range=(10, 20)).query()Another complication is what to do when there is no suffix - i.e. the user just wants an exact match. The problem is there are different operators for this - equals for numeric attributes, exact_match for certain text attributes, and some text attributes don't even accept exact_match. So far, we have been able to blissfully ignore the Big List Of Allowed Terms and trust the user to just provide them correctly, but now we are stuck - we need information from this schema in the library itself in order to be able to construct these queries correctly. We could go back to having the user provide the operator directly, but again this requires them to understand more about how the underlying API works than we should be bothering them with. We have to add the schema to the library.

Schema Management

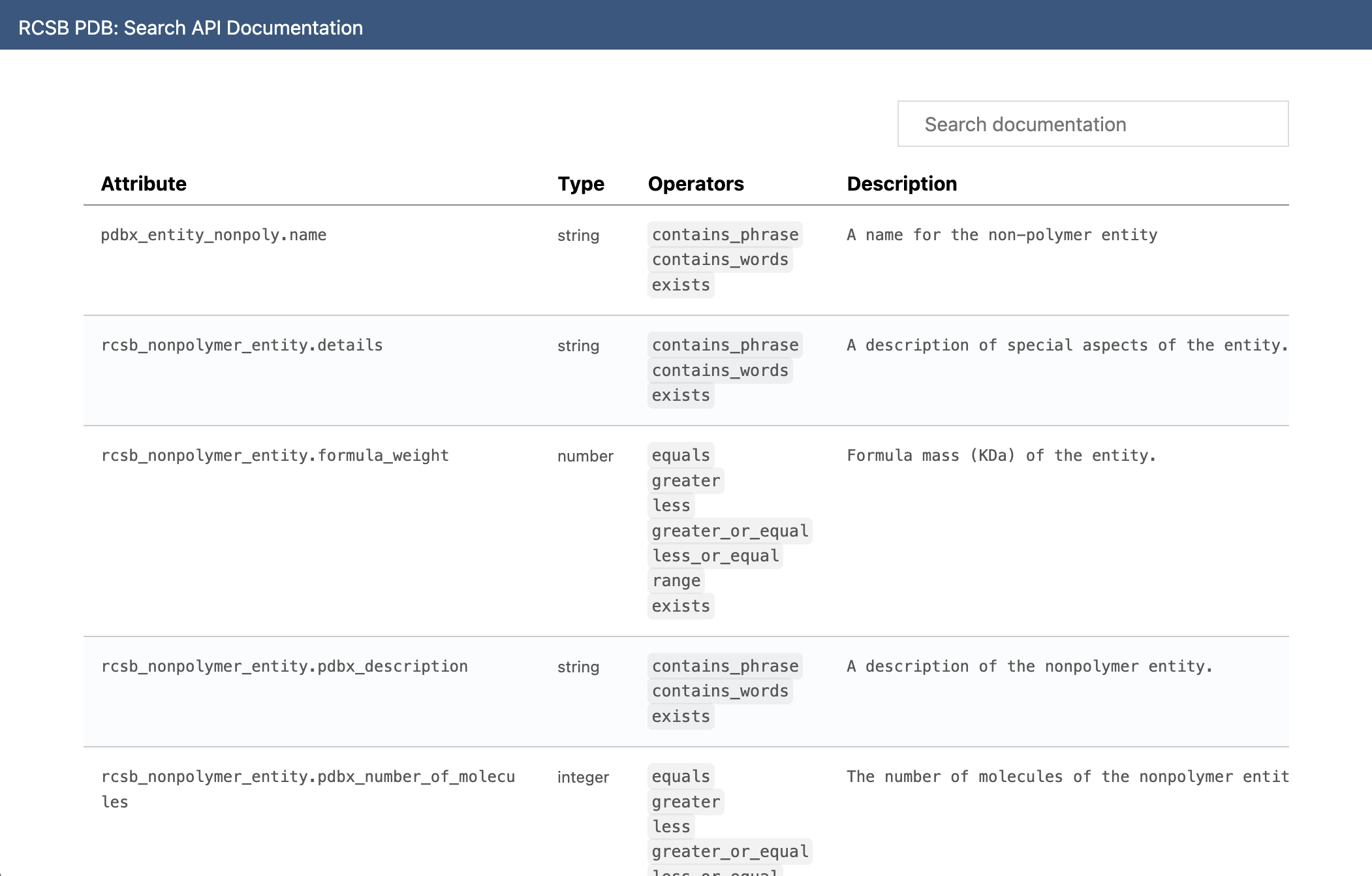

The available attributes, and the operators each of them support, are available on a HTML page on rcsb.org. This is exactly the information we need.

The easiest way to incorporate this information would be to scrape it and produce a mapping of attribute names to available operators, and add this to the library. Then, when no operator is provided, we use this list to determine whether to use equals, exact_match or contains_phrase.

There are a few issues with this approach though - the primary one being that if the schema changes, the library is out-of-date. Users won't be able to use newly added terms as they would be rejected as being invalid, and each version of the library would be stuck on whatever the schema happened to be when it was published.

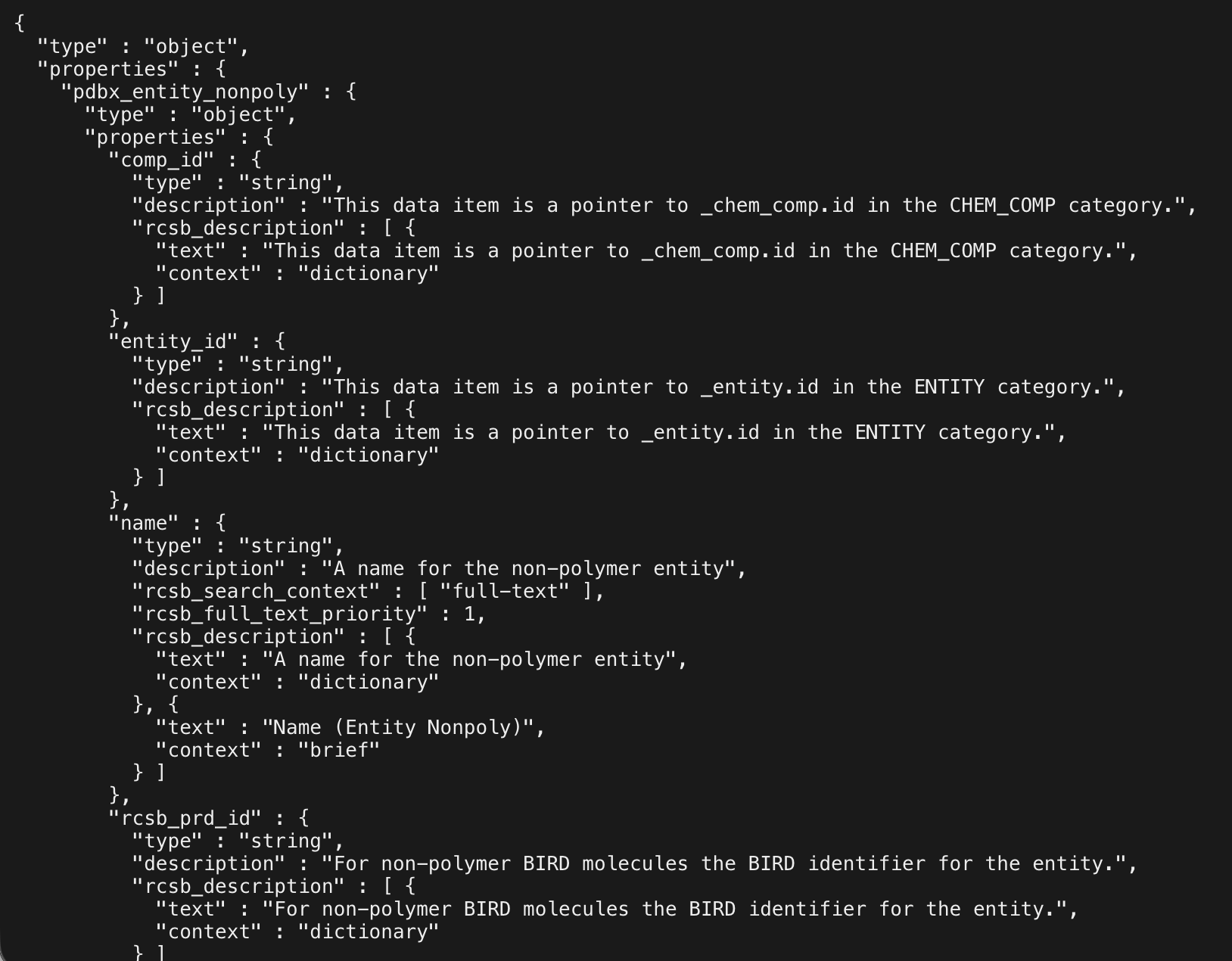

The library needs some way of updating its own understanding of what the current schema is, and for that we need both a hardcoded representation of this schema, and functions which can download the schema and process it dynamically to get the latest version of the schema. And while scraping HTML is fine for a one-off script that isn't part of the library, if this is going to be a core part of pdbsearch, we need something a bit more reliable. Fortunately, the schema for the text service is also provided as a JSON schema object, at a different URL.

The size of this JSON is actually quite substantial, and we don't want 99% of the library's size to be this one JSON object - but there's a lot of information here that we don't need, so fortunately it is possible to recursively traverse this object to get something like this:

TEXT_TERMS = {

"pdbx_entity_nonpoly.name": [

"full-text"

],

"rcsb_nonpolymer_entity.details": [

"full-text"

],

"rcsb_nonpolymer_entity.formula_weight": [

"default-match"

],

"rcsb_nonpolymer_entity.pdbx_description": [

"full-text"

],

...These terms determine the operators that are valid for each attribute.

But what to do with this functionality? How do we use it to keep the hardcoded schema up to date? Any code in the library's __init__.py module will be executed every time the library is first imported - so we can just try to fetch this information on first load, update the hard-coded dictionary in terms.py, have it fail silently if there's an issue, and in theory the library's own schema will always be up to date.

But... we can still do better. This solves the original problem, but now every time the library is imported there is a noticeable 1s or so pause while it does this. One second isn't a huge problem, but in reality 99% of the time it will be a one second pause for nothing. The schema isn't going to change very often. We can have the check be optional by letting the user prevent it with an environment variable, but the user shouldn't even have to think about any of this. So, we can just cache it locally. Every time the library is imported, it checks for this local cache, uses that if it is newer than some cutoff (currently 24 hours), and if not it tries to fetch a new one and saves that.

Finally, we will want to update the hard-coded terms anyway in future versions, and for that we need an easy way to access the functionality we have created for downloading the schema. So, we can add two simple CLI commands - one for downloading the processed schema and saving it to file, and one for manually clearing the local cache:

pdbsearch schema > text.json

pdbsearch schema --indent=4 > text2.json

pdbsearch clearschemaThis is done by adding a __main__.py file to the library to let it be executed like a script, and then updating setup.py to register pdbsearch as a shortcut for python -m pdbsearch.

So the final approach for handling this schema is:

- We hard-code the current mapping of metadata attributes to valid operators into the library source code.

- Whenever the library is imported we try to get the current latest version of this schema from the online JSON reference, failing silently and falling back to the hard-coded reference if this fails.

- We cache this downloaded schema representation locally so that we only need to look for an update once every 24 hours.

- We provide a CLI tool for downloading the information we need, so that we can update the hardcoded schema every time we release a new version.

And with that, our text_node function works exactly as it needs to.

Combining Nodes

We now have the ability to create query nodes for any of the search services, and execute them. But each node can only do one query. The real power of the RCSB search API is that it lets you combine any number of nodes, in any combination of AND and OR logic. For example, consider this example from the API's documentation, which returns all polymers in structures since 20th August 2019 which are either human or mouse in origin:

{

"query": {

"type": "group",

"logical_operator": "and",

"nodes": [

{

"type": "group",

"logical_operator": "or",

"nodes": [

{

"type": "terminal",

"service": "text",

"parameters": {

"operator": "exact_match",

"value": "Homo sapiens",

"attribute": "rcsb_entity_source_organism.taxonomy_lineage.name"

}

},

{

"type": "terminal",

"service": "text",

"parameters": {

"operator": "exact_match",

"value": "Mus musculus",

"attribute": "rcsb_entity_source_organism.taxonomy_lineage.name"

}

}

]

},

{

"type": "terminal",

"service": "text",

"parameters": {

"operator": "greater",

"value": "2019-08-20",

"attribute": "rcsb_accession_info.initial_release_date"

}

}

]

},

"return_type": "polymer_entity"

}Here 'group nodes' are used to bundle other nodes which are all to be combined using a single AND or OR. Group nodes can be nested within other group nodes, and you can essentially construct a query of any complexity you like here.

Currently pdbsearch doesn't support this because it only has individual terminal nodes. We need separate object types for both group and terminal nodes, and a common base class which would contain the shared logic for executing. Something like this:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from pdbsearch.queries import query

class QueryNode(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def serialize(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def and_(self, node):

pass

@abstractmethod

def or_(self, node):

pass

def query(self, return_type, **request_options):

return query(return_type, self, **request_options)

@dataclass

class TerminalNode(QueryNode):

service: str

parameters: dict

def serialize(self):

return {

"type": "terminal",

"service": self.service,

"parameters": self.parameters

}

@dataclass

class GroupNode(QueryNode):

logical_operator: str

nodes: list[TerminalNode]

def serialize(self):

return {

"type": "group",

"logical_operator": self.logical_operator,

"nodes": [node.serialize() for node in self.nodes]

}The logic for executing the query is the same for both types, but they each have different serialization methods. We also need to define what actually happens when and_ or or_ is called. Clearly the result will always be a new GroupNode, but we can be a little clever with simplifying the eventual structure. If a terminal node 'ands' a group node that is itself an 'and' group node, the resulting group node can just have a flat list of child nodes, the original group node doesn't need to be kept.

This now lets us do this:

node1 = pdbsearch.full_text_node(term="thymidine kinase")

node2 = pdbsearch.text_node(pdbx_struct_assembly__details__not__contains="good")

node3 = pdbsearch.sequence_node(protein="MALWMRLLPLLALLALWGPDPAAA")

node4 = pdbsearch.sequence_node(dna="ATGCATGCATGC")

node5 = pdbsearch.sequence_node(rna="AUGCAUCGAUGC", identity=0.95, evalue=1e-10)

node = node1.and_(node2).or_(node3.and_(node4.or_(node5)))

results = node.query("entry", return_all=True)We can now perform any search query that can possibly be made against the API.

The high-level search function

The user can now make very complex queries, as above, or they can make very simple queries like this:

results = pdbsearch.full_text_node(term="thymidine kinase").query("entry")But something about this simple query doesn't sit right with me. The user just wants to do a simple search for a piece of text, but (1) we are requiring them to know which service they want to use (full-text) in this case, which they shouldn't need to know or care about for a simple query like this, and (2) they have to call two functions, as the original one just returns a node object and, again, unless they are making complex queries, why do they need to know or care about this?

We started with a clean, simple search function, then delved into nodes and node-specific query functions as we understood more about the API worked. We do need this functionality, and we do need to let the user construct queries in this way - but equally that isn't always a level of complexity the user needs. We want to let the user use a simple interface that hides all this complexity, while giving them the option to traverse 'down' the hierarchy of complexity to the underlying mechanisms if and only if they need to.

We can do this by re-introducing that simple, top-level search function, which is a layer of abstraction above manual node construction. It would take any parameter that is valid for any of the node functions, as well as any of the return options, construct all the nodes itself, and combine them with 'and'. So you could do either of these or anything in between:

# Simple

results = pdbsearch.search(term="thymidine kinase")

# Or multiple queries

results = pdbsearch.search(

return_type="polymer_entity",

term="thymidine kinase",

chem_comp__formula_weight__lt=1000,

pdbx_struct_assembly__details__not__contains="good",

protein="MALWMRLLPLLALLALWGPDPAAA",

dna="ATGCATGCATGC",

rna="AUGCAUGCAUGC",

identity=0.95,

evalue=1e-10,

structure="4HHB-1",

operator="relaxed_shape_match",

entry="4HHB",

residues=(("A", 10), ("A", 20)),

rmsd=0.5,

exchanges={("A", 10): ["ASP"], ("A", 20): ["HIS"]},

smiles="CC(C)C",

inchi="InChI=1S/C6H12/c1-2-4-6-5-3-1/h1-6H2",

match_type="graph-relaxed-stereo",

rows=50,

start=100

)In this last example, multiple nodes get created by internal query function calls - the function goes through each keyword argument and works out which service type they are for (and therefore which function to use), and creates a single AND group node. It also passes the request options in to get fifty results, starting from the hundredth. How this is done is somewhat complex (it has to intelligently group related operators, know which is for which node function etc.) but the interface is presents to the user is very simple.

We also specify the return_type here to override the default of entry, but we can also define utility functions search_polymer_entities, search_assemblies etc. as alternatives...

def search_entries(**kwargs):

return search("entry", **kwargs)

def search_polymer_entities(**kwargs):

return search("polymer_entity", **kwargs)

def search_assemblies(**kwargs):

return search("assembly", **kwargs)

# etc.More request options

With the search functionality itself more or less final now, let's see if we can incorporate any more of the request options that RCSB supports. We added pagination and the ability to return all results earlier, but it is easy to add the rest:

- Sorting - probably the most useful option, the API supports a list of text-service terms and their direction, structured as

[{"sort_by": "rcsb_accession_info.initial_release_date", "direction": "desc"}]. We can make this easier by letting the user simply add a-to the front, and construct the dictionary ourselves. We can also let the user just provide a string if only searching by one term. - Counts-only - if you only want to know the number of results without actually seeing them, all the search API lets you provide a

return_countsflag. This is straightforward to add as acounts_onlyparameter. - Content-types - RCSB stores experimental structures (those produced by physical experiments to determine atom locations) and computational structures (structure predictions, such as those produce by Alpha-Fold). By default it just returns the former, but you can opt to return both types, or just computational structures, using the

"results_content_type": ["computational", "experimental"]flag. We don't need to do anything complex here - just add acontent_typesparameter that passes whatever is given to this attribute. - Facets - this is a somewhat complex feature of the search API that lets you specify how results should be grouped/binned. I made a judgement call here to support this by adding a

facetsattribute that just passes whatever is given to the"facets"request option, without delving into the details of how it works. In a future version of pdbsearch, perhaps we can do something more interesting here.

Publication

That's it. All of the functionality of the web search API is now exposed through this library, and there are three hierarchical layers of abstraction for users of the library to access at the level they need:

- A simple

searchfunction, for just getting results with one function call. - Helper functions for making individual nodes, for control over the boolean logic

- Direct access to underlying

QueryNodeobjects for complete control over how the request is constructed.

I have omitted some parts of the process, such as the test suite (which was written alongside the source code itself), setting up the GitHub CI, handling non-200 HTTP codes, the docstrings, and the documentation itself (a mix of docstring text rendered into HTML, as well as human written overview information walking a user through the different features). You have been a patient enough reader already, and I don't think documenting this as well would have added much.

The library is now published as version 0.5.0, the documentation is live at pdbsearch.samireland.com and the source code is at samirelanduk/pdbsearch. May it, or this account of its creation, be useful to you.